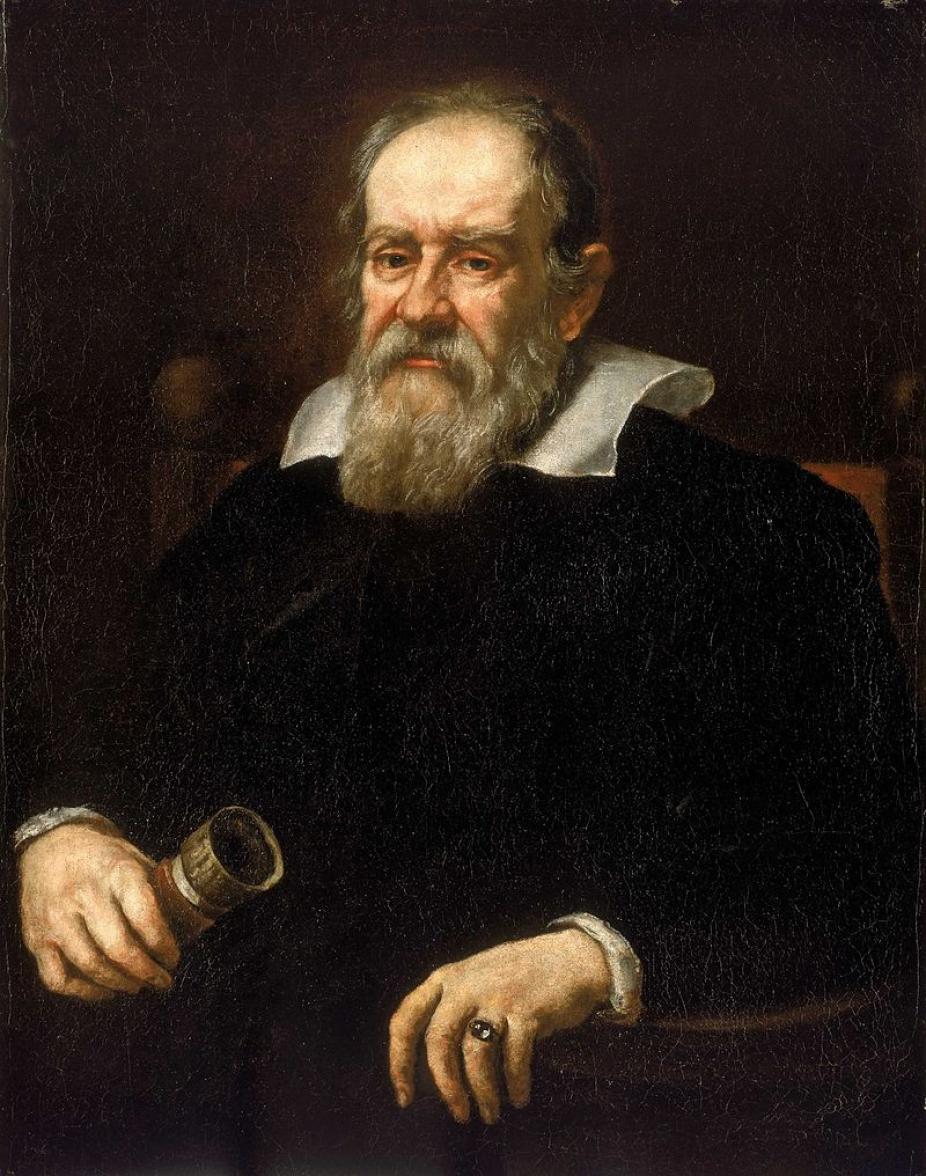

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642)

Galilei was born February 15, 1564 in Pisa, to a declining family of Florentine patricians. In 1581 he was sent to study medicine at the University of Pisa, but never showed much interest in the subject and starting in 1583 devoted himself exclusively to mathematics and philosophy. He left Pisa without a degree, yet in July 1589 he was appointed to the chair of mathematics at that same university. In 1592 he took on the prestigious chair of mathematics at the University of Padua.

Portrait of Galileo Galile by Justus Sustermans

Royal Museum Greenwich Collection Blog

Prior to 1609, Galileo had only shown passing interest in astronomical matters, despite privately presenting himself as a Copernican. His research while at Pisa and Padua was mostly concerned with the problem of motion, in particular motion on inclined planes, of the pendulum, and of freely falling bodies. First little known outside of Italy, Galileo' s telescopic discoveries in 1609 and 1610 instantly propelled him into international fame, and won him a position at the Florentine Court, as chief mathematician and philosopher to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo de Medici II.

Galileo's telescopic discoveries, published in his landmark 1610 book "Sidereus Nuncius" shook the very foundations of the Ptolemaic/Aristotelian cosmology. His observations of the Moon's surface revealed valleys and mountains, instead of the smooth perfectly spherical surface postulated by Aristotle. His observations of multitudes of faint stars gave some credence to Copernicus' suggestion that the universe may be a lot larger than previously believed. Perhaps his most striking discovery was that of four moons orbiting Jupiter, in direct contradiction with another Aristotelian postulate, that of the Earth being the center of (circular) motion for all heavenly bodies.

In the following two years Galileo made two new sets of observations that would further undermine the prevailing Aristotelian/Ptolemaic cosmology. The first was the observation of the phases of Venus, and the second the observation of sunspots. Galileo published his views on the latter in his "Three Letters" to Mark Wesler, in response to the three letters written earlier by Christoph Scheiner to Wesler. As detailed below, controversy over who received credit for the discovery of sunspots would later turn Scheiner and Galileo into bitter enemies.

Following the 1616 decree suspending the publication of "Copernicus' De Revolutionibus" pending revisions and an injunction by Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino not to hold or defend the Copernican doctrine, Galileo turned to the problem of the tides, hoping to provide a proof of the motion of the Earth. Galileo's pro-Copernican campaign culminated with the publication of his 1632 "Dialogue" concerning the two chief world systems. The Roman ecclesiastic authorities considered the book to violate the 1616 decree. In September 1632 Galileo was summoned to Rome by the Inquisition and was put on trial.

Galileo's 1633 trial (painting by Cristiano Banti, 1857).

On June 22, 1633 Galileo was forced to kneel in front of the "Roman Inquisition" and recant his beliefs in the Copernican doctrine and the motion of the Earth. He was then sentenced to life imprisonment, which was almost immediately commuted to perpetual house arrest without visitors, ostensibly for having disobeyed a 1616 injunction by Cardinal Bellarmine not to defend or teach the Copernican doctrine. "Galileo's Dialogue" was put on the Index of Prohibited Books, as well as "Copernicus' De Revolutionibus" and the books of Johannes Kepler dealing with planetary theory.

Galileo's sentence was upheld rather rigidly despite appeals to the Inquisition and the Pope by Galileo himself, as well as numerous prominent scientists and statesmen in Italy and Europe. After Galileo became blind in 1637, the enforcement of his sentence was relaxed somewhat, and he was allowed to receive visitors for extended periods of time. In 1638 he completed yet another landmark work, "Discourses on Two New Sciences," which provided the foundations for the modern science of mechanics. The manuscript was smuggled out of Italy and the book published in Holland.

Galileo died on the evening of January 8, 1642. The Roman ecclesiastic authorities vetoed the public funeral and honor planned by the Florentine state. His books, together with those of Copernicus and Kepler, were removed from the Index in 1835. Only in 1992 did the Roman Catholic Church formally admit to having erred in dealing with Galileo.

Bibliography

Drake, S. 1978, Galileo at work: His scientific biography, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press (1995 Dover reprint).

De Santillana, G. 1955, The crime of Galileo, The University of Chicago Press.

Fantoli, A. 1996, Galileo, Vatican Observatory Publications [distributed outside of Italy by the University of Notre Dame Press].

Galileo, G. 1610, Sidereus Nuncius, trans. A. van Helden 1989, The University of Chicago Press.

Galileo, G. 1613, Letters on Sunspots [in S. Drake (trans.) 1957, Ideas and Opinions of Galileo], Doubleday.

Galileo, G. 1632, Dialogues concerning the two chief world systems, trans. S. Drake, 2nd edition 1967, University of California Press.

Sharratt, M. 1994, Galileo: Decisive Innovator, Cambridge University Press.

Galileo's Drawings and Writings

Moon drawings

Drawings of the moon as seen with Galileo's telescope. Drawing reproduced from Galileo's 1610 "Sidereus Nuncius."

By his own account, Galileo first observed the Moon on November 30, 1609. Comparing patterns of light and shadow in the vicinity of the terminator (the dividing line between light and shadow) at first and third quarter, Galileo could argue convincingly that there exists mountains and valleys on the lunar surface. Aristotelian doctrine stipulated that celestial bodies were perfectly smooth and spherical.

The first telescopic observations of the Moon on record were carried out by the Englishman Thomas Harriot (ca. 1560-1621), on the evening of July 26, 1609. However, based on his extant correspondence and entries in his notebooks, as in the case of sunspots, Harriot did not appear to have drawn any particular physical significance from what he saw.

Bibliography

Galileo, G. 1610, Sidereus Nuncius, trans. A. Van Helden 1989, The University of Chicago Press.

Whitaker, E.A. 1978, Journal for the History of Astronomy, 9, 155-169.

Sketches of faint stars

Sketches of faint stars in the Orion constellation, as seen by Galileo through his telescope. Reproduced from Galileo's 1610 "Sidereus Nuncius."

The larger stars with a central dots are those visible to the naked eye, with the topmost three corresponding to the so-called belt of Orion. That the universe contained many more stars than previously known gave moral support to the idea that it may also be a lot larger than assumed up to then. This idea had been advanced by Nicolaus Copernicus himself as a possible explanation for the lack of observed annual parallax in the fixed stars.

Bibliography

Galileo, G. 1610, Sidereus Nuncius, trans. A. Van Helden 1989,The University of Chicago Press.

Sketch of Jupiter's moons

Sketches of the four moons of Jupiter, as seen by Galileo through his telescope.

What Galileo saw are the four larger moons of Jupiter, now known as Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. The drawing depicts observations from the time period January 7 to January 24, 1610. Galileo had considerable difficulty in recognizing the true meaning of what he was seeing; Callisto often lay out side the (restricted) field of view of his telescope, Io often lost in Jupiter's glare, and some moon occasionally disappeared in Jupiter's shadow or behind or in front of the planet itself.

Galileo named the moons Medicean Stars, after the ruling Florentine family Medici. This was a move calculated to improve his chances of moving back to Florence, and it succeeded. The names used today were coined by Simon Mayr (1573-1624), who for a time claimed priority on their discovery.

Bibliography

Debarbat, S., and Wilson, C. 1989, The Galilean satellites of Jupiter from Galileo to Cassini, Roemer and Bradley, in The General History of Astronomy, vol. 2A, eds. R. Taton and C. Wilson, Cambridge University Press, pps. 144-157.

Dialogue

Title page of Galileo's "Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems", published in Florence in 1632. Reproduced from S. Drake's 1967 translation.

This is usually considered as Galileo's masterpiece. Despite ostensible claims to the contrary, the Dialogue represents Galileo's strongest endorsement of the Copernican system over its Ptolemaic counterpart, and makes devastating refutations of many central tenets of Aristotelian Physics. The book still makes for fascinating reading today.

On July 25, 1632 the Roman authorities issued an order forbidding further distribution of the book, and recalling copies already distributed. Following Galileo's trial and condemnation in 1633, the “Dialogue” was put on the Index of Prohibited Books, where it remained until 1835.

Bibliography

Galileo, G. 1632, Dialogues concerning the two chief world systems, trans. S. Drake, 2nd edition 1967, University of California Press.

Discourses

Title page of Galileo's "The Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences", published in 1638.

“The Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences” (Discorsi e Dimostrazioni Matematiche Intorno a Due Nuove Scienze), published in 1638 was Galileo's final book and a scientific testament covering much of his work in physics over the preceding thirty years.

After his “Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems,” the Roman Inquisition had banned the publication of any of Galileo's works, including any he might write in the future. After the failure of his initial attempts to publish Two New Sciences in France, Germany, and Poland, it was published by Lodewijk Elzevir who was working in Leiden, South Holland, where the writ of the Inquisition was of less consequence.

Discourses was written in a style similar to Dialogues, in which three men (Simplicio, Sagredo, and Salviati) discuss and debate the various questions Galileo is seeking to answer. There is a notable change in the men, however; Simplicio, in particular, is no longer quite as simple-minded and stubborn an Aristotelian as his name implies. His arguments are representative of Galileo's own early beliefs, as Sagredo represents his middle period, and Salviati proposes Galileo's newest models.

Bibliography

Galileo, G. 1638, Discourses on two new sciences, trans. S. Drake 1974, The University of Wisconsin Press.

Letters on Sunspots

Title page of Galileo's "Letters on Sunspots", published in Rome in 1613.

The Letters were written to the wealthy Augsburg Magistrate Mark Wesler (1558–1614), a well-known patron of the new sciences, in response to Christoph Scheiner's own Letters on Sunspots, published through Wesler in 1612. The lynx depicted on the Title page indicates Galileo's membership in the Lincean academy (Accademia dei Lincei, for the "sharp-eyed"), the first scientific academy in Europe. The academy was founded 1603 by Prince Federigo Cesi, and was conspicuous in granting membership to a small number of selected intellectuals operating outside the mainstream academic establishment. In April 1611 Galileo became the sixth member elected to the Academy, and to the end of his life would identify himself as a "Lincean" on the title page of all his books.

In his Letters, and unlike Scheiner, Galileo correctly identifies sunspots as markings on the solar surface, as opposed to small planets inside the orbit of Mercury. By studying the position of sunspots on successive days Galileo also inferred that the Sun rotates, and established its rotation period as close to one lunar month. Galileo and Scheiner were later to quarrel bitterly over who received the credit for the discovery of sunspots. In fact, the first recorded sunspot observation is on December 8, 1610 by the Englishman Thomas Thomas Harriott (1560–1621), and the first publication by Johann Fabricius (1587–1616), in the fall of 1611.

Bibliography

Galileo, G. 1613, Letters on Sunspots, trans. S. Drake1957, in Ideas and Opinions of Galileo, Doubleday.

Mitchell, W.M. 1916, The history of the discovery of the solar spots, in Popular Astronomy, 24, 22-ff.

Sidereus Nuncius

Title page of Galileo's "Sidereus Nuncius", published in Venice in 1610. Reproduced from the introductory essay in A. van Helden's 1989 translation.

“Sidereus Nuncius” instantly made Galileo a European celebrity, and earned him the position of chief mathematician and philosopher to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo de Medici II, in Florence in July 1610.

The book described Galileo's groundbreaking telescopic discoveries, including his lunar observations, observations of faint stars invisible to the naked eye, and discovery of Jupiter's four largest Moons. Originally greeted with some skepticism, Galileo's telescopic discoveries benefited from an enthusiastic endorsement by Johannes Kepler and Christoph Clavius (and other Jesuit astronomers at the Roman College).

Bibliography

Galileo, D. 1601, Sidereus Nuncius, trans. A. van Helden 1989,The University of Chicago Press.